#5 of 7 articles about impacts of Covid-19 on supply chain innovation

Most of the innovations are product range enhancements and operational improvements driven by product development and operations teams. These process and incremental innovations are keeping a company abreast or ahead of competition. But true change is brought about by disruptive innovation. It is the “reinventing us”, the self-disruption and gradual self-destruction, the critical move that changes the playing field to our advantage that makes true change. Innovations like Dell’s make-to-order approach which stood out to the make-to-stock processes of other computer manufacturers or Apple’s smartphone. Irrespective of incremental or disruptive innovation, it all begins with the groundwork.

The first step is to look at our pain points and gaps to understand where innovation may be needed. An order to cash cycle perceived as too long or a high out of stock rate. Or a gap in our service offering. Companies usually have three options to create a solution: make, partner, or buy. In other words companies can leverage internal resources to develop solutions in-house or let teams create their own venture entity. They can use an external service provider or partner with an innovator outside. Or they invest in a business to secure a stake in the future.

How the innovator sees it

Partnering and investing requires an understanding of the options that are available. The outcome of this mapping exercise is determined by a company’s DNA. Why? Companies with operating genes look for the established providers and choose the one with the best fit. Innovators, instead, see in the situation an opportunity to leapfrog. While they care also about improving the present their primary goal is to create the future.

Innovators include not only established providers but also ventures into the mapping of available options. This helps them to understand what is out there and where the developments are pointing towards. This allows them to benchmark their “today” against possible “tomorrows”. The benefit of the innovator approach is that fresh perspectives can emerge. That unknown unknowns can become known. The result can be the decision to postpone the effort as some new technologies appear on the radar which allows us to pivot into a new way of operating. But these ideas are not yet that clear or are not proven at the time.

Routes to startup investing

But patience is also not in an innovator’s blood. An initial step could then be to engage in a proof of concept (PoC) project. While the PoC is progressing, they can work on a specific strategy and the corporate venture capital (CVC) team might consider an investment. The PoC can lead to a service contract or an investment, but also to an innovative strategic partnership to jointly build a solution or product for the incumbent. As an example, adidas has partnered with Spotify to create adidas go in 2015.

Solving pain points and closing gaps is one reason to invest. Another starting point is a market thesis. The set of assumptions that describes the way industries may look like in 20xx. This helps to sketch out future industries and business models.

Internal incubators can help with ideation and prototyping. Cisco’s legendary spin-in approach is another option. This route to innovation is about an internal team of engineers that is sent out to create a venture to build a solution. The venture is funded by the incumbent, sometimes in partnership with other investors. With the achievement of predefined milestones, the ownership of the parent company increases until the venture is totally spun in. Launching – internally or externally – or investing into venture companies can help to establish the foundations or secure the building blocks for the future business model or enterprise derived from the thesis of the market.

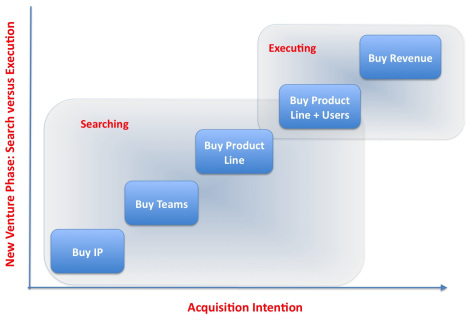

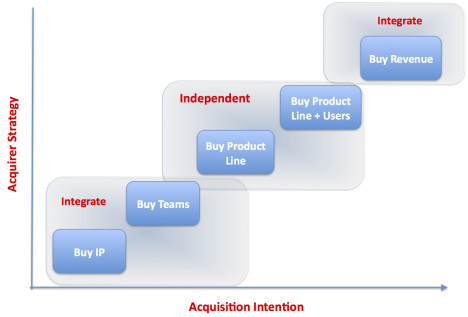

Also important is that the corporates understand what they are engaging with. When incumbents just buy intellectual property (IP) and talent, quick integration may be the way to go, although the mindset of the individuals may not fit and function in a large company environment. But when a corporate is investing in a company that is in search of its product/market fit, its go-to-market strategy and the business model that can scale, and you want the venture to grow, preserving its startup culture is paramount. A formal or a de facto integration would destroy its value. Ventures in growth mode require autonomy.

A few lessons learned

Whether motivated by the wish to improve operational processes and close product gaps or by the desire to create the future business model, there are some ground rules to follow to increase the chances of success. Lessons learned will help to validate and substantiate the investment case and extract the value after the completion of the investment deal. Four key lessons learned drive successful corporate investments.

The first one is that it is important to set up an independent venture capital (VC) arm. Many corporates tend to invest off a balance sheet. The consequence is that the corporate ventures are beholden to strategic priorities and corporate governance. This approach holds the entrepreneurs back from making their necessary moves and bets. They are always playing second fiddle to the host. Dynamic ventures require space to scale and mature their solutions.

The second lesson is that the best investments transform the existing or build a new business. Many corporate venture capital (CVC) funds were established to “learn” about the trends in innovation, the latest market developments and what is going on in the broader ecosystem. Learning about change is certainly a desirable objective, but it should be an outcome of investing, rather than the reason for it. A solid rationale is built around a good business case or a strong concretized vision.

The third lesson is that investing in innovation is about the future. Many corporates use the traditional VC approach to invest in what is, rather than in what could be. One reason for this may be the lack of blue ocean thinking. Or the fear of disrupting oneself. But if we do not disrupt ourselves, someone else will. Bosch Ventures invests well ahead of areas that may be directly relevant to Bosch to explore new opportunities.

The fourth lesson is that most ventures need companionship. Just allocating capital is not enough. Entrepreneurs need favorable conditions and support to become successful. CVCs should be the vehicle that brings the incumbent, but more importantly ventures into the desired future. The priority is to help grow the ventures, even if the ‘child’ starts cannibalizing our own business threatening the ‘mother ship’. In fact, disruption should be welcomed as the ultimate success of a venture investment.

When taking a majority or control stake in a venture, corporates can offer to leverage their internal or external partner accelerators to provide – for a period of up to six to twelve months – mentorship, industry knowledge, exposures to customers and introductions to partners that can help with product development, PoCs and commercialization. Entrepreneurs happily accept this kind of support, provided they stay in control.

Successfully investing in ventures is the result of a solid proven process and an entrepreneurial mindset. Picking the wrong target brings us on the route of despair. But we will suffer an even bigger pain when applying corporate thinking to venturing. Startups are run by a different logic than corporates. They can absorb capital for a decade. Make a lot of mistakes. Ventures are far from being perfect. But this is also not their goal.

We cannot manage venture investments in a corporate way; entrepreneurs struggle to handle bureaucracy, heavy planning processes and slow decision-making. Ventures cannot even pay for what is considered necessary within corporates. Most ventures are dependent on external financing. But funds should go into product development, commercialization and growth.

Ventures are like ”babies”, “children”, and “adolescents”. Good parenting is not an easy task. It is a responsibility. Experts can help corporates with building the technical skills but more importantly adjusting their mindset and achieving the mental strength necessary to grow and let go a child we should have prepared for thriving in its own world. Our children are our future.

In 1958, the average lifespan of companies listed in Standard & Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) was 61 years. Today, this number has come down to 18. Experts estimate that the typical company lasts about ten years before it is acquired, merged, or liquidated. Hence, achieving operational excellence and building new businesses should be at the core of our strategies.

Source graphics: https://steveblank.com/2014/04/23/corporate-acquisitions-of-startups-why-do-they-fail/

Leave a Reply