#4 of 7 articles about the electrification of goods transport

While electric heavy-duty trucks and long-haul transport still face some technology and commercial challenges, electric light commercial vehicles (eLCVs) with weight of under 3.5 tons seem to be the logical next step towards the electrification of goods transport in our cities. ELCVs appear as a rapid response to traffic-related emissions and meet the goal of “essentially CO2-free city logistics in major urban centres by 2030”. An ambition set in The 2011 European White Paper for Transport.

The general interest is high but eLCVs have struggled to build high demand so far. “Over 70 percent of surveyed fleet managers plan to acquire eLCVs in the near future, mostly driven by their ambition to reduce fleet emissions. However, only a small share of them has actually acquired an electric LCV,” finds the 2019 Arthur D. Little paper The German market for battery-electric light commercial vehicles – The challenge of electrifying urban transport. “Our analysis shows that current generation eLCVs have a hard time competing with diesel vehicles in these categories due to battery range limitations, charging requirements and a significantly higher price tag,” continuous the report. In Germany, only about 4,900 eLCVs were newly registered in 2018. 85% of those vehicles where StreetScooters, designed, built, and deployed by Deutsche Post DHL. The German logistics giant that has just announced that it will cease the in-house development of electric vehicles before the end of the year.

At the same time, William Todts, Executive Director, Transport & Environment, an non-governmental organization (NGO), campaigning for cleaner transport in Europe says: “We want to see a deadline set for the end of the internal combustion engine in Europe and a coordinated, proactive push on the part of government, industry and consumers to get there. We believe a “Green New Deal” for transport to be the most effective way to not only combat climate change, but to make it an inclusive undertaking from which everyone benefits. This way, “zero emissions” becomes a rallying cry not just for urban elites, but for people in the suburbs, rural areas and peripheral regions of the European Union, too.”

ELCVs are the centerpiece of sustainable urban transport. But application of eLCVs seems to be scarce. The literature on ex-post-analysis from real cases in eLCVs is limited. Why are we hesitant to drive the electrification of urban transport? What is it that stands in the way of large-scale adoption of eLCVs? Much of the concerns expressed center around three points: the availability of electric vehicles, public and private charging infrastructure, and the economics of electric fleets.

Availability of vehicles

Thirty companies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have sent a letter to the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, calling for ‘ambitious’ sales targets for zero-emissions trucks and vans. The 30 signatories that include Unilever, REWE and AB InBev claim that the current supply of electric and hydrogen trucks and vans is ‘nearly non-existent’ and this would prevent them to decarbonize road transport. They also request the European Union’s (EU) 2030 emission reduction target to be raised to 55% and the bloc to become climate-neutral by 2050.

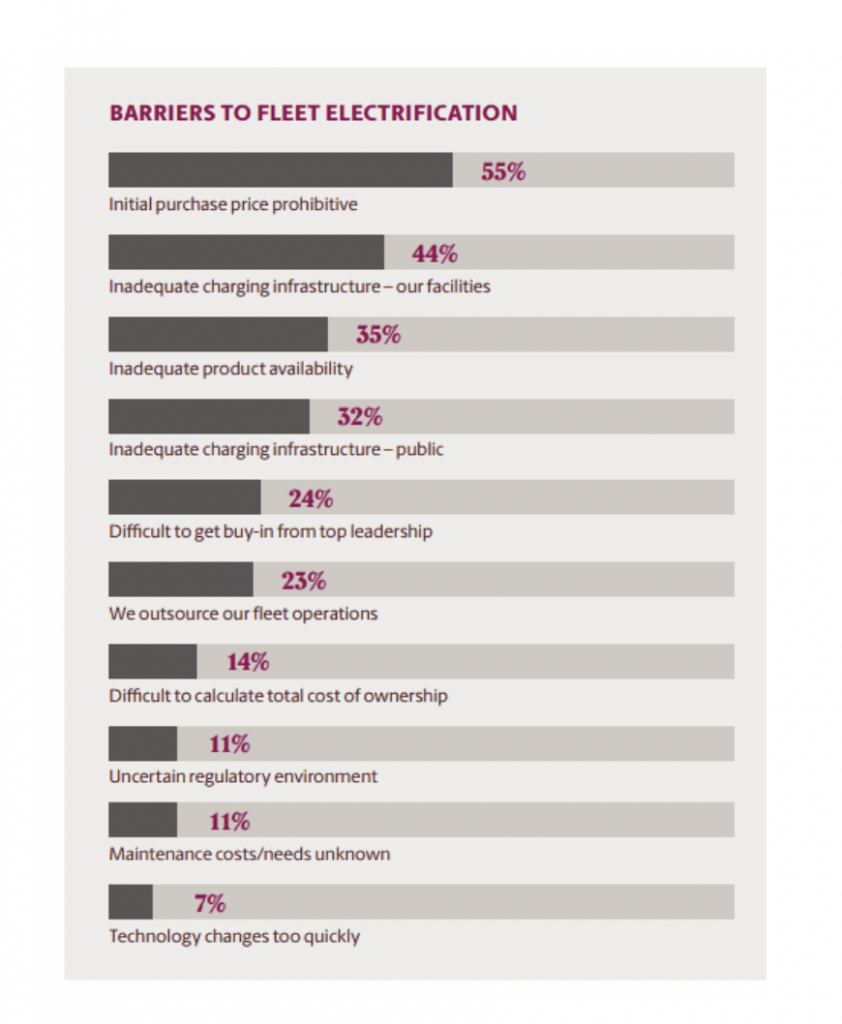

In a UPS/GreenBiz research study, 35% of respondents from large and 41% of smaller organizations cited “Inadequate product availability” as a top barrier to electrification. While the interviewees recognize that electric vehicle technologies are becoming more available and affordable, medium- and heavy-duty commercial electric technologies are still not available at scale. Automakers and startups have entered the electric vehicles market, including Arrival, Chanje, Daimler, Hyliion, Thor Trucks, TransPower and Workhorse. However, many companies, such as Tesla with its Semi truck, are only taking pre-orders, which creates uncertainty about the availability and feature set.

Typical eLCV users operate vehicle fleets in urban environments that drive less than 200 kilometers per day and return to a depot or platform in the evening. According to the research by Arthur D. Little, the majority of eLCV owners were satisfied despite compromises in day-to-day operations. The report states that over two-thirds of the panelists were either “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with their eLCVs. Most of fleet managers surveyed explained that eLCVs fell short when unplanned route changes and sudden customer requests demanded longer driving ranges. Public fast-charging networks and battery swapping technologies help to overcome these challenges.

Charging infrastructure

Electric commercial vehicles are regularly marketed as part of a system solution. Vehicles are bundled in services to facilitate operation and the transition to the new technology. ELCVs often come with a home or depot charging solution as market offering. Vehicle manufacturers provide customers – directly or via partners – hardware to recharge batteries at their own premises. Access to public charging networks is rather an exception in the eLCV offering. In urban logistics, onsite charging solutions suffice to cover the regular needs of fleet operation. Battery swapping during the loading process extends the daily range of vehicles that return to the platform during the day.

Source: UPS

Building charging infrastructure requires an understanding of electrical capacity and projections of future charging requirements. The infrastructure needs to be cost effective and convenient. Compared with a diesel fleet, a facility hosting a fleet of 200 to 300 electric trucks requires up to four times the power. Companies prioritize locations that offer financial incentives to deploy their electric fleets. Collaboration with local utilities can help to evaluate and develop charging strategies. They can advise fleet managers on rate structures and site tariffs.

Economics of electric fleets

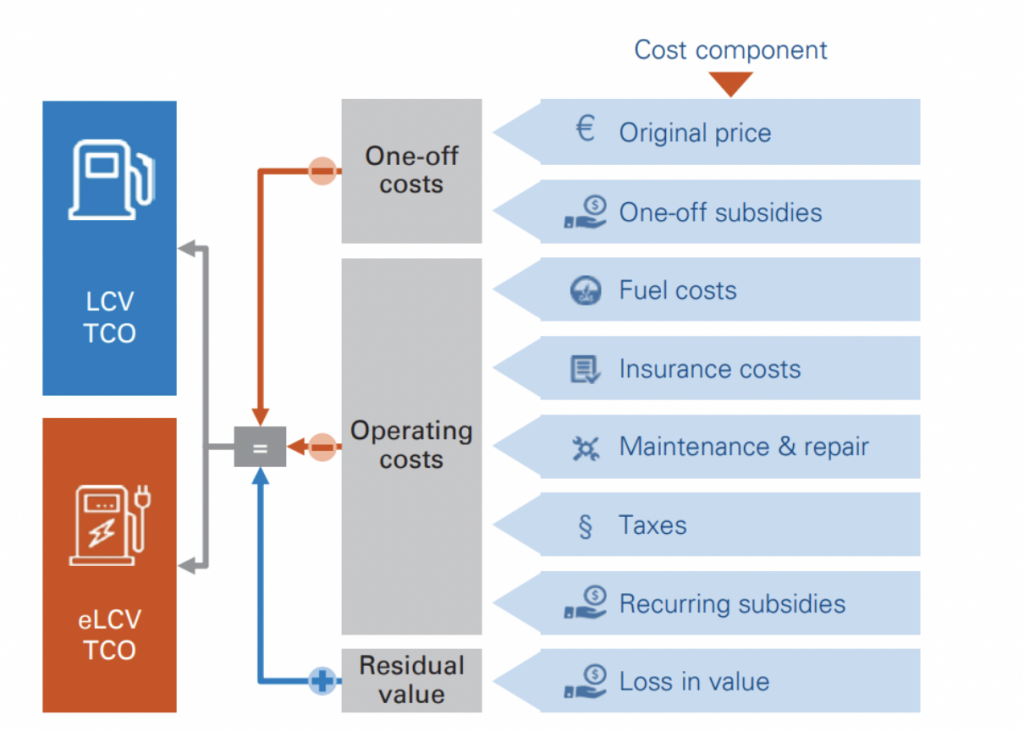

Kellen Schefter, senior manager, sustainable technology, EEI states: “We have to recognize that there is still an upfront cost premium for the technology we’re looking at largely driven by the battery cost. We have a good opportunity on fuel costs to save operational money. But the question is, is that fuel cost and maybe the maintenance cost savings, enough to compensate for the upfront purchase prices of the vehicle to make the total cost of ownership work?” The cost savings are related to distance and routes driven, type of terrain, as well as the geographic distribution and types of vehicles. New planning tools are required. Electric vehicles (EVs) are two to three times more efficient than conventional gasoline-powered vehicles. EVs are said to cost 23% less to service and maintain than internal combustion engine (ICE) models over three years.

“The locations where we put electric trucks first are where we’re able to fully utilize the battery range capability – a significant factor in the return on investments. We are purchasing 50 medium duty electric trucks, and we anticipate those vehicles will be at cost parity with conventional gas diesel,” says Patrick Browne, director of global sustainability at UPS.

Many companies justify the cost for fleet electrification through the total cost of ownership (TCO). A model that looks at the direct indirect financial costs and savings over the lifetime of the vehicle. The TCO advantage ranks high in the list of reasons to move to electric vehicles. Other main motivations to switch from diesel to eLCVs are better eco-friendliness and access to financial incentives for electric vehicles, such as subsidies and tax exemptions.

Certainly, nascent technologies have their pros and cons. With scale electric vehicle technology will further mature and prices will decline. The 2018 Bloomberg New Energy Finance Electric Vehicle Outlook reports that from 2010 to the end of 2017, average lithiumion battery prices dropped by 79 percent while average energy density of EV batteries improved at 5-7 percent per year. Government incentives, grants and tax breaks can help where market mechanisms do not yield the necessary financial results yet. Battery rental service can also contribute to reduce the initial purchase price allowing to sell electric vehicles without batteries – which represent a significant price component.

The debate around the three concerns shows that there is significant room for optimism – particularly in the field of eLCVs in the context of electric urban logistics. Over the mid to long run solutions for heavier duty commercial vehicles and long-distance transport will also mature.

With vision and new skills and capabilities, we can accelerate the electrification of the commercial vehicle fleet. However, every stakeholder group needs to go the extra mile. In 2019, Amazon has announced plans to purchase 100,000 electric vans as part of its pledge to go carbon neutral by 2040. These are the kind of bold moves the world needs to achieve the ambitious goals set by international organizations, governments, cities, and companies.

Leave a Reply